It was the only

thought my adrenaline-charged, near-panicked mind could summon. “Three rock

climbers had to be rescued last night off Monitor Rock near Twin Lakes just

east of Independence Pass. Reportedly, the group was stranded when their rope became

stuck as they were rappelling from the 450-foot-tall rock.” Something like that.

People on their couches at home would guffaw and grumble “idiots” before clicking

around for something better. Now that we’d been in our predicament for over an

hour, this scenario seemed not just possible, but likely.

On the positive

side, we were on a solid ledge that had not one but two bolted anchors. At ten

feet long, two feet wide and three-hundred and fifty feet off the ground, was

it comfortable? No. But at least we were in no danger of falling. It was autumn,

however, and evening was approaching. Though it had been a warm, bluebird day,

once that sun went down it was going to get cold.

“We can think

this through,” said my wife, Ella, sounding much calmer than I felt. ‘There is

no reason to panic.”

“I also have

this,” added my friend and often climbing partner, Trent. He reached into his

backpack and retrieved a Spot Satellite GPS messenger. With one touch of the

panic button, this little device would transmit an S.O.S along with our

coordinates to emergency dispatch, and the finest in backcountry rescue services

would be deployed to save us. But how long would it take them to arrive?

Monitor Rock was 26 miles from Leadville, where it was likely any such rescue

operation would be staged. The amount of time it would take to mobilize and travel

here alone could be hours. Then they would have to climb to us, and get us

down, and do whatever follow-up was required. I was guessing we’d be lucky to

get home by midnight.

“Are we at that

point?” I asked, watching his finger edge closer to the button. The three of us

were silent. There was only so much pulling one could do on a stuck rope before

giving in to the harsh reality.

Ella sighed. “We

might be.”

I swore out

loud, which didn’t help anything. The climb itself, a historical multi-pitch

traditional route known as the Trooper Traverse (5 pitches, 5.8+) had smooth.

We’d swapped leads and made our way up the enjoyable line in decent time, even taking

the more-difficult 5.9 crux variation for the final pitch. The setting for Monitor

Rock was breathtaking, especially with the golds, oranges and yellows of fall

at their peak. The cobalt sky was dotted with friendly, paintbrush clouds and

the perfectly warm air was so still we could hear calls of “take” and

“lowering” from the climbers cragging on other routes far below us at the base

of the wall. I hated the stark juxtaposition of all that beauty against our

current predicament.

“All right,” I

said to Trent with a deep breath. “I guess we have to do it.”

Trent nodded and

touched his thumb to the panic button.

*

|

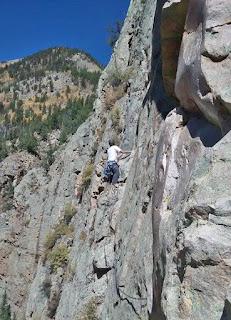

| Ella on rappel right before the accident |

Rappelling is a special type of

descent that can speed up our progress and allow us to cruise past gnarly

sections that would be difficult or impossible to downclimb. Duane Raleigh,

publisher of Rock & Ice magazine

and first ascensionist of many Western Colorado rock climbs, asserts in his

article “Rappelling- Surviving Climbing’s Diciest Business” that “of the myriad

ways to kill yourself climbing, rappelling is the quickest.” This grim truism

echoes through my head every time I fix myself to a rope to begin a rappel

descent.

When done properly, however, rappelling

is quite simple, easy and generally safe, but the consequences of any broken

link in the chain are disastrous. There are many ways rappelling can go wrong,

including anchor failure, knot failure, improper connections with the belay

device, loss of brake-hand control, failure to tie backup knots, rappelling off

the end of the rope, and more. One of the most common rappelling faux pas,

however, is getting a rope stuck when pulling it.

Now, there is an advantage to this

mistake over the others: you are at the bottom of the rappel when it happens.

If it were just a single rappel then at worst you have to leave your expensive

rope behind and hope you can come back for it later. But on a multi-rappel

descent, getting your rope stuck up high can leave you stranded with hundreds,

sometimes thousands, of feet still to the ground.

*

“Let me try it one more time,” said

Trent, slipping the GPS tracker back into his bag. Taking both ends of the

rope, he began to saw the two lines back and forth.

At first, nothing would budge. Then

suddenly, a hundred feet above us, the knot popped free from whatever it had

been stuck on, and began pulling through the anchor. A minute later it hiss

down the smooth granite and landed our feet.

We stared at it with our mouths

hanging open in shock. After more than an hour being stranded, we were free. We

cheered. We hugged. We celebrated. No hours-long rescue. No Channel 5 News

story. No being benighted on a two-foot-wide ledge at night at 10,000 feet

elevation. We were going home.

|

| Monitor Rock on Colorado's Independence Pass |

“Let’s get out of here,” Ella said

after we packed up our bags. She started the march down the trail in the

direction of our car.

“I couldn’t agree more,” added

Trent and followed.

I looked back at sweeping heights

of Monitor Rock. Evening was already almost at hand and the glistening gray

rock was falling into shadow. I could still pick out the ledge where we had

spent an hour stranded. I couldn’t help but think how close we’d come to still

being up there.

“Maybe we need to go get a beer,” I

added. I turned away from the rock to follow the others, and didn’t look back.

Opinions are like, hmm... well, everybody has one. Want to share yours? Visit my Speculative Worlds Forum

All writing is the original work of Brian Wright and may not be copied, distributed, re-printed or used any form without express written consent of the author.

Find out here how to CONTACT me with publishing and/or use questions

No comments:

Post a Comment